As part of some clustering work and learning about hidden Markov models, I’ve been doing some reading about the EM algorithm and it’s applications. It’s a pretty neat algorithm (I love iterative algorithms like Newton’s method and the Euclidean algorithm) so I thought I’d illustrate how it works.

I’ve also been doing a bit more python recently, so I thought I would do all this in python rather than R. However, this post is still done in RMarkdown using python code chunks! I know Jupyter notebooks have their fans, but as an authoring tool RMarkdown is plain text which makes it easier to create/edit documents and maintain them via tools like Git (unlike Jupyter notebooks).

The Basic Idea

Like any iterative algorithm, the big picture behind the EM algorithm is to converge to values given some initial guess. For our purposes, we want to converge to the parameters of a Gaussian mixture model given observed data, a number of Gaussians being mixed, and guesses for the initial means and standard deviations of the mixture components. This is one of the major practical uses of the EM algorithm: determining unknown parameters of mixture model components.

The algorithm repeats two key steps: Expectation and Maximization. The expectation step calculates probabilities of each data-point being in a mixture component. The maximization step uses these probabilities to update (a) means and standard deviations of mixture components and (b) the proportion of data-points in each component. There’s not much here that’s special to the case of Gaussian mixture models (GMM’s), except where we use normal distributions and the parameters we compute in the maximization step.

Note: The following functions are intended to be easy to understand as opposed to highly optimized with great error handling. If you’re estimating components of a Gaussian Mixture model in a production environment, Scikit-Learn has excellent clustering routines that will be far more robust and efficient than anything here.

Expectation Details

The expectation step computes the probability of a data point being in any one of the mixture components. If is the data-point, the mean and standard deviation for component and the fraction of data-points in component , then these probabilities are:

This can be turned in the following python code (as well as some libraries we’ll need throughout the post):

import numpy as np

import pandas as pd

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import seaborn as sns

import scipy

from scipy.stats import norm

def expectation_probabilities_gmm(data, mean_vect, sd_vect, fracPerComp):

ret_probs = np.zeros([len(data),len(mean_vect)])

for i in range(len(data)):

for j in range(len(mean_vect)):

ret_probs[i,j] = (fracPerComp[j]*norm.pdf(data[i],mean_vect[j],sd_vect[j]))

ret_probs[i,:] = ret_probs[i,:]/np.sum(ret_probs[i,:])

return(ret_probs)This will return a numpy array with one row per data-point and one column per mixture component, where values are the probabilities. Clearly, we have to supply the data, and previous values for the means, standard deviations, and fraction of points per component. Initially, these will be our guesses, but subsequent iterations will get them from the maximization step.

Maximization Details

Once we have a new batch of probabilities, we need to update values for the mixture model parameters. First, we calculate a component weight for each component which is the column sum of our probability array. We then use the component weight to compute weighted means, standard deviations, and fractions of points per component.

Here’s a python function that computes these and returns the tuple given the data and expectation probabilities:

def maximization_params_gmm(expect_probs, data):

clust_weights = [np.sum(expect_probs[:,j]) for j in

range(np.shape(expect_probs)[1])]

new_means = np.divide([np.sum(expect_probs[:,j]*data[:]) for

j in range(np.shape(expect_probs)[1])],clust_weights)

new_sds = np.divide([np.sum(expect_probs[:,j]*(data[:]-new_means[j])*(data[:]-new_means[j])) for j in range(np.shape(expect_probs)[1]) ], clust_weights)

new_sds = np.sqrt(new_sds)

new_frac = np.divide(clust_weights,np.shape(expect_probs)[0])

return new_means, new_sds, new_frac;Note that this is for a mixture of univariate Gaussian distributions, in higher dimensions you would need covariance matrices to be computed rather than just standard deviations.

Stopping Criteria

A key part of an iterative algorithm is when to stop, which is achieved in the EM algorithm by looking at the convergence of the log-likelihood. Although in this post we’ll just run a fixed number of iterations.

def log_likelihood(data, mean_vect, sd_vect, fracPerComp):

ret_probs = np.zeros([len(data),len(mean_vect)])

for i in range(len(data)):

for j in range(len(mean_vect)):

ret_probs[i,j] = (fracPerComp[j]*norm.pdf(data[i],mean_vect[j],sd_vect[j]))

row_sums = np.sum(ret_probs[i,:])

loglike = np.sum(np.log(row_sums))

return(loglike)Observed Mixture Data

I don’t have a nice real-world GMM dataset, but we can easily manufacture some:

np.random.seed(seed=123987) #reproducibility

vals = [np.random.normal(5, .5, 100), np.random.normal(3, 1, 100), np.random.normal(6.5,1.25,100)]

grps = ['A','B','C']

#build dataframe

df = pd.concat([pd.DataFrame({"group":grps[i], "value":vals[i]}) for i in range(0,3)], axis=0, ignore_index=True)Initially I had written this with 3 separate vectors of values and 3 data-frames that I then glued together. Then I remembered one of my favorite things about python: list comprehensions! Clearly I’ve made heavy use of them in the above functions as well.

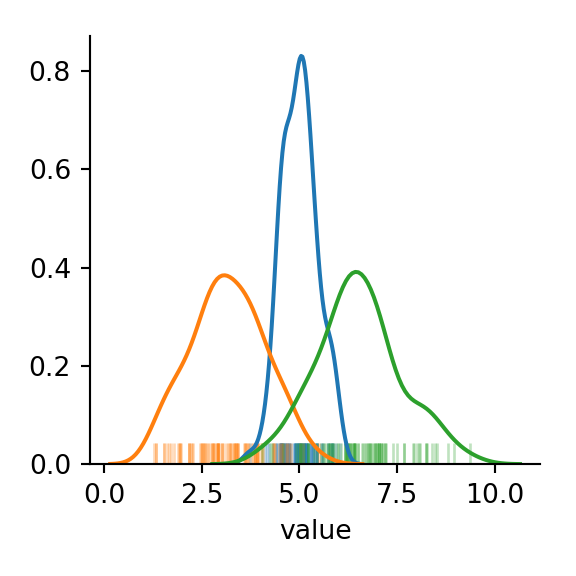

With the group column in our dataframe, we can easily see the three components of the mixture:

#grouped

plt.figure(figsize=(3,3))

plots = sns.FacetGrid(data=df, hue="group", legend_out=True)

plots.map(sns.distplot,'value', kde_kws={"shade":False},rug_kws={"alpha":.3}, rug=True, kde=True, hist=False)

plt.show()

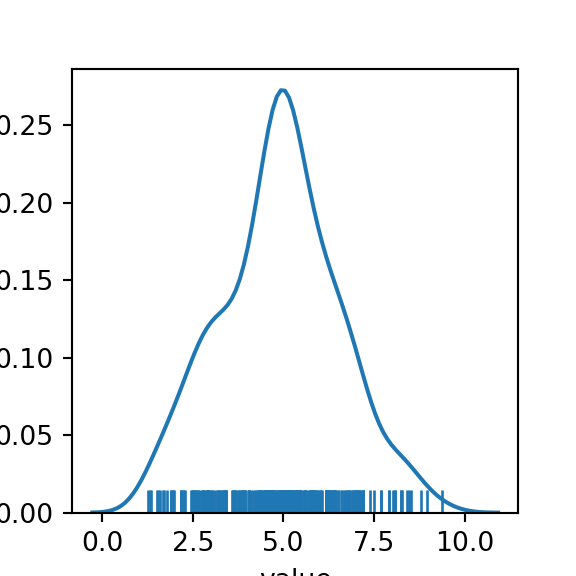

In practice though, we would only be able to see the full distribution of our data:

plt.close() #get a blank plot rather than overlay on our last distplots

plt.figure(figsize=(3,3))

sns.distplot(df['value'], rug=True, kde=True, hist=False)

plt.show()

The “shoulders” on the curve given a hint that we may be dealing with an underlying mixture model of 3 components. But how “non-normal” is our data? We can run a Shapiro-Wilkes test and compare with the same number of points sampled from a single normal distribution to get an idea.

##Shapiro-Wilkes test

print(scipy.stats.shapiro(df['value']))## (0.9909396767616272, 0.0613214448094368)The second value in this tuple is the p-value associated to a null hypothesis that our data is from a single normal distribution. In this case we would fail to reject that our observed data is different from a sample from a single normal distribution at the customary significance level. More evidence that p-values and significance tests can miss important details.

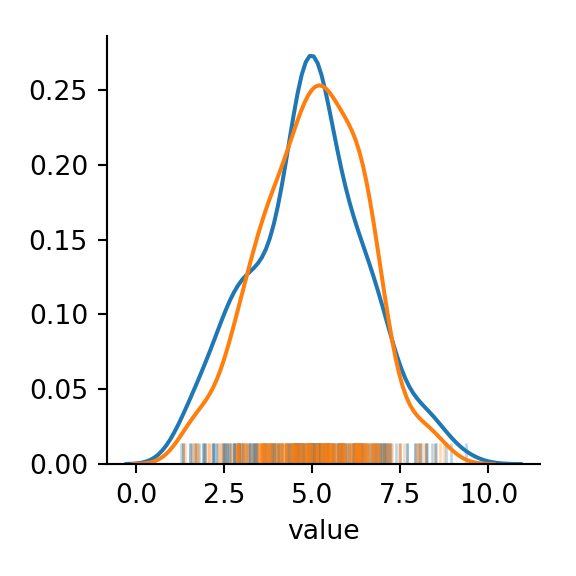

We can also compare to simulated data sampled from a true normal distribution with the same mean and standard deviation as our observed data to see how close our data is to being normal.

##compare with true normal sample

simDF = pd.DataFrame({"type":"simulated", "value":np.random.normal(df['value'].mean(), df['value'].std(), 300)})

simDF = pd.concat([pd.DataFrame({"type":"sample", "value":df['value']}), simDF], axis=0, ignore_index=True)

plt.figure(figsize=(3,3))

plotsim = sns.FacetGrid(data=simDF, hue="type")

plotsim.map(sns.distplot,'value', kde_kws={"shade":False},rug_kws={"alpha":.3}, rug=True, kde=True, hist=False)

plt.show()

Running The EM

Here’s a function to handle calling the E and M steps and holding the results of each. This will be handle to look at how the process converges.

def run_em(data, init_means, init_sds, init_frac, num_iterations):

ret_means = np.zeros((num_iterations,len(init_means)))

ret_sds = np.zeros((num_iterations,len(init_means)))

ret_fracs = np.zeros((num_iterations,len(init_means)))

ret_ll = np.zeros(num_iterations)

ret_means[0,:] = init_means

ret_sds[0,:] = init_sds

ret_fracs[0,:] = init_frac

for i in range(num_iterations-1):

ret_ll[i]=log_likelihood(data, ret_means[i,:],ret_sds[i,:], ret_fracs[i,:])

new_probs = expectation_probabilities_gmm(data, ret_means[i,:],ret_sds[i,:], ret_fracs[i,:])

ret_means[i+1,:], ret_sds[i+1,:],ret_fracs[i+1,:] = maximization_params_gmm(new_probs, data)

return ret_means, ret_sds, ret_fracs, ret_ll;Now we can make some guesses and run the EM algorithm. Based on the distribution of all the data, it looks like there are irregularities around 3, 5.5, and 7 - so those will be our means. We’ll assume variance of 1 and equal size for all groups.

means = [3,5.5, 7]

sds = [1,1,1]

fracs = [1/3,1/3,1/3]

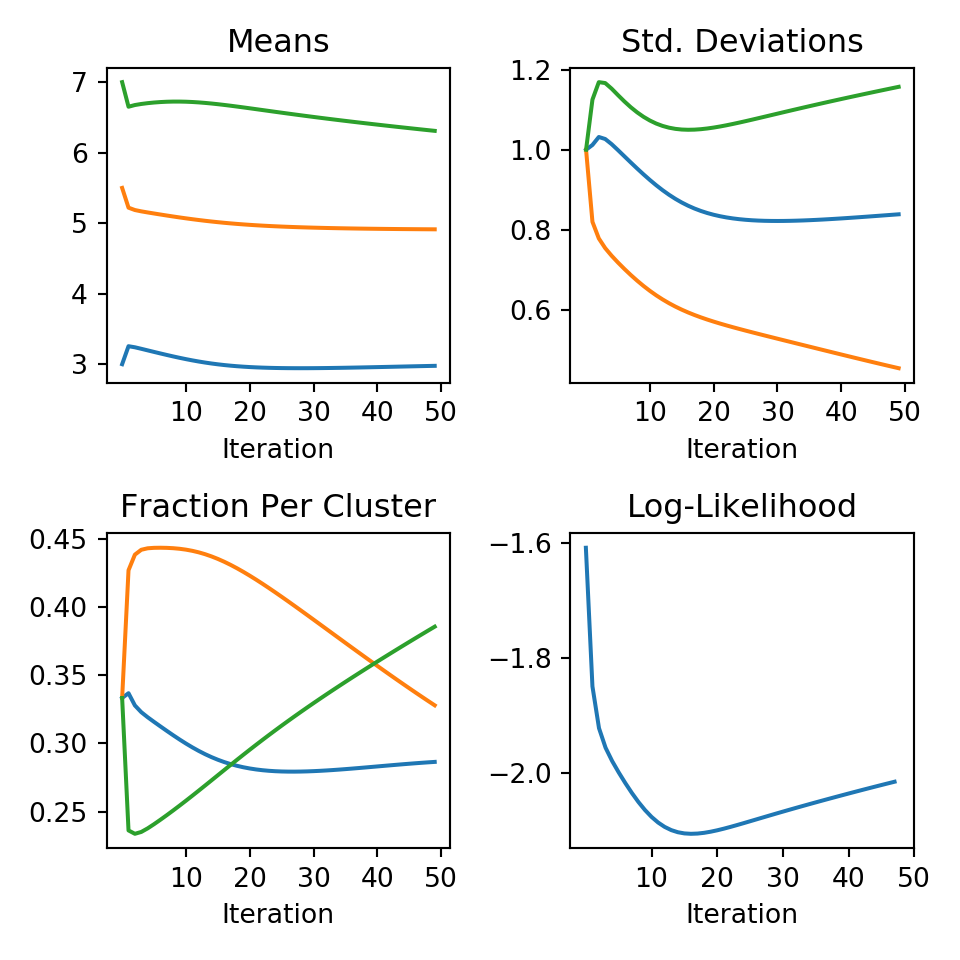

mu,sigma,frac,ll = run_em(df['value'], means, sds, fracs, 50)We can then easily use matplotlib to see how these change over the iterations:

plt.figure(figsize=(5,5))

plt.subplot(2,2,1)

plt.plot(mu)

plt.title("Means")

plt.xlabel("Iteration")

plt.xticks([10*(i+1) for i in range(5)])

plt.subplot(2,2,2)

plt.plot(sigma)

plt.title("Std. Deviations")

plt.xlabel("Iteration")

plt.xticks([10*(i+1) for i in range(5)])

plt.subplot(2,2,3)

plt.plot(frac)

plt.title("Fraction Per Cluster")

plt.xlabel("Iteration")

plt.xticks([10*(i+1) for i in range(5)])

plt.subplot(2,2,4)

plt.plot(ll[0:48]) #last ll value hasn't been calculated

plt.title("Log-Likelihood")

plt.xlabel("Iteration")

plt.xticks([10*(i+1) for i in range(5)])

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

This looks like we had convergence fairly quickly, except the fraction of points per cluster - but our y-scale is very narrow. In the end our estimates are:

print("Means:", mu[49,:])## Means: [2.9767655 4.91279169 6.30925586]print("Std. Dev.:", sigma[49,:])## Std. Dev.: [0.83852695 0.45363153 1.15733853]print("Fraction per Cluster:", frac[49,:])## Fraction per Cluster: [0.28652637 0.32794345 0.38553017]Since our mixture components had means and standard deviations we did pretty good. The main difference is the points where the normal distributions overlap with “high” probability. This is where any clustering algorithm will break down. Despite how close our data was to a single normal distribution, the EM algorithm was able to divide the observations into 3 groups with means and standard deviations almost equal to the actual cluster parameters.

I want to show some visuals of our mean and std. dev. estimates with the data and how the clusters evolve, but this post has gotten a little long. Look forward to part 2 soon…